The smallest pixels ever made could be used for new types of flexible displays big enough to cover an entire building. It is said that these pixels created are a million times smaller than those found in smartphones that are made by trapping particles of light under small rocks of gold.

The colored pixels were developed by a team of scientists led by the University of Cambridge. The pixels are deemed compatible with roll to roll fabrication on flexible plastic films, effectively reducing their production cost.

It has been a long-time project to mimic the color-changing skin of squid or octopus, allowing objects or people to disappear into the natural background but making large flexible display screens are still expensive because they are made from highly precise multiple layers.

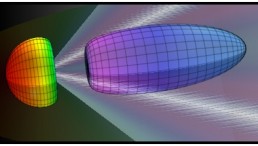

At the center of the pixels is a tiny particle of gold a few billionths of a metre across. The grain is on top of a reflective surface, trapping the light in the gap in between. A thick sticky coating surrounds each grain which change chemically when electricity switched, causing the pixel to change its color across the spectrum.

To dramatically drive down production costs, the pixels are made from cating vats of golden grains with an active polymer called polyaniline. It is then sprayed with a flexible mirror-coated plastic.

The pixels are known to be the smallest ever created; it is said to be a million times smaller than the smartphone pixels. These pixels can be seen in bright sunlight and they do not need constant power to keep their set color because they have an energy performance that can make areas sustainable and feasible.

"We started by washing them over aluminized food packets, but then found aerosol spraying is faster," said co-lead author Hyeon-Ho Jeong from Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory.

"These are not the normal tools of nanotechnology, but this sort of radical approach is needed to make sustainable technologies feasible," said Professor Jeremy J Baumberg of the NanoPhotonics Centre at Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory, who led the research.

"The strange physics of light on the nanoscale allows it to be switched, even if less than a tenth of the film is coated with our active pixels. That's because the apparent size of each pixel for light is many times larger than their physical area when using these resonant gold architectures."

![Sat-Nav in Space: Best Route Between Two Worlds Calculated Using 'Knot Theory' [Study]](https://1721181113.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/53194/258/146/50/40/sat-nav-in-space-best-route-between-two-worlds-calculated-using-knot-theory-study.png)