After COVID-19 revealed the weaknesses of the supply chain, many retailers and manufacturers sought alternative supply chains to replenish inventory quickly due to increased consumer demand. In this paper, we will discuss the most popular alternative supply chain models.

The most common supply chain models, although cost-effective, are lengthy and slow. Beginning with manufacturing, overseas or domestically, inventory is transported to the manufacturer's distribution center, where it may be repackaged before being moved to regional distribution centers. From these distribution centers, inventory could be further allocated and repackaged, depending on the final retailer. From the regional distribution center, the repackaged inventory is moved closer to the final customers, where it will be distributed to retailers and sold.

The supply of healthcare products, including toilet paper, PPE, hand sanitizer, masks, and others, was severely impacted by COVID-19 as manufacturers overseas were decimated as COVID-19 infected millions of people throughout the world. Manufacturing slowed and, in many cases, halted completely. Customer demand increased, leading to shortages, which manufacturing was slow to fulfill. Not all shortages were due to increased customer demand. While certain categories had increased demand (for example, Hand Sanitizers, Masks, et cetera), shortages of toilet paper can be traced to panic shopping, and other items (like apparel and kitchen appliances) came to a halt from manufacturers closing factories. According to a November 30, 2023 press release from the White House, "It became clear that global supply chains were propagating micro shocks into macro-level effects."[1] (Issue Brief: Supply Chain Resilience | CEA, 2023) Full production was slow to return as further variations caused more delays overseas.

Other supply chain issues were found within manufacturing supply chains. A lack of raw materials decreased the total amount of products that could be made. The global chip shortage is an example of this, as a limited number of game consoles[2] and vehicles[3] were available to consumers.

To combat future interruptions in supply chains, manufacturers and retailers have turned to alternative supply chain models to meet consumer demands. The supply chain models discussed herein are the most popular ones employed.

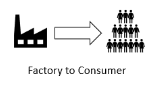

Factory to Customer

The factory-to-customer channel is where the products are shipped from the manufacturing floor directly to the final customer. Products are shipped directly to the customer without the use of distribution centers or retail storefronts. This is not to be confused with dropshipping (direct-to-consumer). Tesla[4], Caspar, and Warby Parker are prime examples of factory-to-consumer. Seattle Chocolates, which makes the chocolates in its factory in Tukwila, WA, has a storefront in its factory[5]. Factory to Customer is better for the environment while saving money on middlemen and continuous shipping from place to place before reaching the final destination.

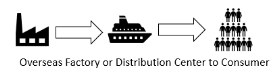

Overseas Manufacturing Distribution Center to Consumer

The overseas manufacturer will sell directly to consumers, storing ready-to-ship products in their distribution centers. The growth of platforms like Shein and Temu are examples of this supply chain model and primarily cater to consumers who are more interested in price than in the speed of shipping. The key to their low prices is the elimination of middlemen. The risk of this supply chain model can be read in reviews of both apps, which have concerns over product quality and long shipping times[6].

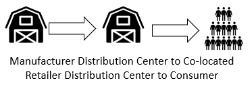

Distribution Center in a Distribution Center

In this model, retailers open a distribution center within the manufacturer's distribution center. Finished products are transferred from one part of the warehouse to the retailer's side, where they are then sold and shipped to customers. Amazon has had a partnership with Procter & Gamble since 2010, in which Amazon set up retail distribution centers within seven of P&G's distribution centers. This partnership has given Amazon direct access to goods made by P&G, which it can then ship directly to consumers. This model has been so successful for Amazon that they expanded to a lot more vendors, including Kimberly-Clark, Seventh Generation, and Georgia Pacific Corp[7].

Dropshipping

Perhaps the most widely known alternative supply chain model, dropshipping or direct-to-consumer, differs from traditional supply chains in that the retailer selling the products never physically houses the products themselves. Retailers list products and then order from the manufacturer once they've received an order on their end. Retailers are responsible for listing and dealing with customer service. For retailers short on space, the dropship supply chain model allows for even larger items to be sold. However, the benefits of dropshipping include a reduced barrier to entry into the ecommerce space, allowing both small and large businesses to compete. Wayfair began as a small dropshipper. The pitfalls of dropshipping stem from retailers using manufacturer distribution centers overseas.

Manufactured on Demand

In this model, manufacturers and retailers only store the raw materials, and the product is made based on demand. This is not a new concept, as both large and small items have been produced in demand for several years. Again, Amazon is an example. For a majority of books sold on Amazon, those books are printed as orders come in. This model offers increased flexibility as well as a more efficient use of raw materials. This model can be used in the manufacturing of products like soap and candles, where the base is prepared in advance and additives are added as orders are received.

Manufactured in Store

Retailers have begun to experiment with growing produce in-store. Many grocers offer fresh juice made on-site already. This model brings the manufacturer into the store. A supermarket in Germany is testing vertical farming on a micro-scale[8], and a Whole Foods in Brooklyn has a rooftop greenhouse[9]. Manufacturing within the store, in this case growing vegetables and herbs, greatly reduces food waste, which is overall better for the environment. Produce isn't allowed to sit on shelves for days, which may cause consumers to question its freshness. Another peripheral benefit is the ability for consumers and retailers to know exactly where their produce came from and if it is organic or not. Other businesses use this model beyond food; Volkswagen Group, with brands such as Porsche, Lamborghini, and Audi, uses 3D printers in car production[10]. This speeds production and eliminates carbon emissions from shipping and manufacturing simple parts.

By exploring alternative supply chain models, retailers and manufacturers are meeting demand, inspiring innovations in products and processes, and saving time and money, all while reducing waste by eliminating middlemen.

About the Author

Karan Monga, with a dynamic career in technology and a profound academic background, currently leads the development of New Liquidation Channels in Reverse Supply Chain. He earned his MBA degree in Global Supply Chain and Operations Management from the University of South Carolina and a Bachelor's in Electronics and Communication Engineering in India. He has experience in Supply Chain and Operations Management with large multinational companies. His career distinguishes extensive research and development work in Reverse Logistics Management, Supply Chain Disruption Management, and Automation in Operations Management. Mr. Monga's expertise bridges multiple disciplines, contributing to significant advancements in technology and Supply Chain.

References

- Issue Brief: Supply Chain Resilience | CEA. (2023, November 30). The White House. Retrieved March 29, 2024, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2023/11/30/issue-brief-supply-chain-resilience/

- Howley, D. (2022, April 20). Why you shouldn't expect to get a PlayStation 5 anytime soon. Yahoo Finance. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://finance.yahoo.com/news/why-you-shouldnt-expect-to-get-a-play-station-5-anytime-soon-160137666.html

- Hawley, D. (2023, July 5). Why Is There A Global Chip Shortage For Cars? J.D. Power. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.jdpower.com/cars/shopping-guides/why-is-there-a-global-chip-shortage-for-cars

- Lame, G. (2021, November 26). Here Is Why Tesla Has No Dealerships. HotCars. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.hotcars.com/here-is-why-tesla-has-no-dealerships/

- Where to buy - Seattle Chocolate Company. (n.d.). Seattle Chocolate. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.seattlechocolate.com/pages/where-to-buy

- Thompson, C., & Tucker, D. (2024, February 27). The billion dollar question: How can Temu sell products so cheaply? CBS News. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/the-billion-dollar-question-how-can-temu-sell-products-so-cheaply/

- Lahiff, A. (2013, October 15). Report: Amazon (AMZN) Partners With P&G (PG) to Sell Direct to Consumers. TheStreet. Retrieved March 29, 2024, from https://www.thestreet.com/markets/amazon-amzn-partners-with-pg-pg-to-sell-direct-to-consumers-12069447

- Peters, A. (2016, March 23). At This Supermarket, The Produce Section Grows Its Own Produce. Fast Company. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.fastcompany.com/3058155/at-this-supermarket-the-produce-section-grows-its-own-produce

- Nguyen, B. (2022, December 31). Inside a Greenhouse on Rooftop of Whole Foods in Brooklyn. Business Insider. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.businessinsider.com/gotham-greens-greenhouse-on-top-of-whole-foods-brooklyn-2022-12

- Volkswagen plans to use new 3D printing process in vehicle production in the years ahead. (2021, June 18). Volkswagen Newsroom. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/en/press-releases/volkswagen-plans-to-use-new-3d-printing-process-in-vehicle-production-in-the-years-ahead-7269

* This is a contributed article and this content does not necessarily represent the views of sciencetimes.com