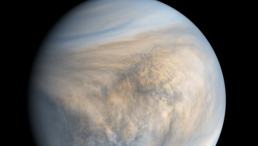

The European Space Agency (ESA) has just published a striking picture of Europa, Jupiter's icy moon. In the image the surface looks like shattered glass; it reveals many interlocking cracks in the moon's icy crust which were formed by an ocean below the moon's surface. Now a team from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) led by planetary scientist Kevin Hand has identified the cracks as sea salt.

Now two new missions to Europa are in the planning stage, one of which may use a lander for surface analysis.

Europa is only slightly smaller than our own moon. Also like Earth's moon Europa is tidally locked, so the same side of it always faces Jupiter. Europa orbits Jupiter every 3.5 days.

Europa is believed to have a surface ocean of salty water, a rocky mantle, and an iron core, like Earth. However, in contrast to any Earthly ocean, Europa's ocean is extremely deep, covering the moon's entire surface. It is also far enough from the sun to ensure that it stays frozen over all over the moon.

Europa's ocean is extremely interesting to scientists because it is warmed by powerful tides thanks to the gravity of Jupiter. These oceans may be favorable to life. Other views of the cracks covering Europa provide more evidence: their yellowish-brown color may indicate the presence of sodium chloride-or common sea salt.

NASA's Galileo telescope has in the past shown us that Europa's color scheme is caused in part by interactions between magnesium and sulfur. This latest study also suggests the presence of sodium chloride-the very substance which dominates the oceans of Earth.

These latest results were produced in the lab, as scientists mimicked Europa's surface conditions. The scientists bombarded sodium chloride with radiation like that emitted from Jupiter inside a vacuum chamber kept at minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit. Several hours of this process is equivalent to about 100 years of radiation from Jupiter, and this produced the same color in the salt as seen in the Europa cracks. The more the salt is bombarded, the darker the color change.

The JPL team describes the experiment which recreates Europa's extreme conditions: "We call it our 'Europa in a can'," Hand says. "The spectra of these materials can then be compared to those collected by spacecraft and telescopes."

"This work tells us the chemical signature of radiation-baked sodium chloride is a compelling match to spacecraft data for Europa's mystery material."

We won't know for sure until the results are confirmed on the moon's surface. With both ESA and NASA planning to make such visits, we may soon have a definitive answer about the potential for life on Europa.