Spaceflight is hard. Blasting heavy cargo, spacecraft, and maybe people to respectable speeds over interplanetary distances requires an amount of propellant too massive for current rockets to haul into the void. That is, unless you have an engine that can generate thrust without fuel.

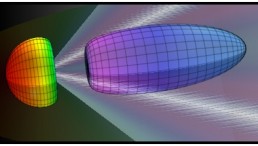

It sounds impossible, but scientists at NASA's Eagleworks Laboratories have been building and testing just such a thing. Called an EmDrive, the physics-defying contraption ostensibly produces thrust simply by bouncing microwaves around inside a closed, cone-shaped cavity, no fuel required.

The device last made headlines in late 2016 when a leaked study reported the results of the latest round of NASA testing. Now, independent researchers in Germany have built their own EmDrive, with the goal of testing innovative propulsion concepts and determining whether their seeming success is real or an artifact.

"The 'thrust' is not coming from the EmDrive, but from some electromagnetic interaction," the team reports in a proceeding for a recent conference on space propulsion.

The group, led by Martin Tajmar of the Technische Universität Dresden, tested the drive in a vacuum chamber with a variety of sensors and automated gizmos attached. Researchers could control for vibrations, thermal fluctuations, resonances, and other potential sources of thrust, but they weren't quite able to shield the device against the effects of Earth's own magnetic field.

When they turned on the system but dampened the power going to the actual drive so essentially no microwaves were bouncing around, the EmDrive still managed to produce thrust-something it should not have done if it works the way the NASA team claims.

The researchers have tentatively concluded that the effect they measured is the result of Earth's magnetic field interacting with power cables in the chamber, a result that other experts agree with.

"In the EmDrive case, interactions with the Earth's magnetic field seems to be the leading candidate explanation of the small thrusts seen," says Jim Woodward of California State University, Fullerton. Woodward has theorized a propulsive device of his own called the Mach Effect Thruster, which the Dresden group also tested.

To determine what's going on with the EmDrive, though, the group needs to enclose the device in a shield made of something called mu metals, which will insulate it against the planet's magnetism. Importantly, this kind of shield was not part of Eagleworks' original testing apparatus either, which suggests the original findings could also be a consequence of leaking magnetic fields.

That sounds like a blow to the concept of the EmDrive, but Woodward is not ready to close the case on the contraption just yet. Aside from the lack of mu metal shielding, the Dresden lab's tests were run at very low power levels, meaning that "any real signal would likely be swamped by noise from spurious sources," he says.

So, perhaps an even more powerful test is what the space doctors ordered to help settle the debate.

![Sat-Nav in Space: Best Route Between Two Worlds Calculated Using 'Knot Theory' [Study]](https://1721181113.rsc.cdn77.org/data/thumbs/full/53194/258/146/50/40/sat-nav-in-space-best-route-between-two-worlds-calculated-using-knot-theory-study.png)